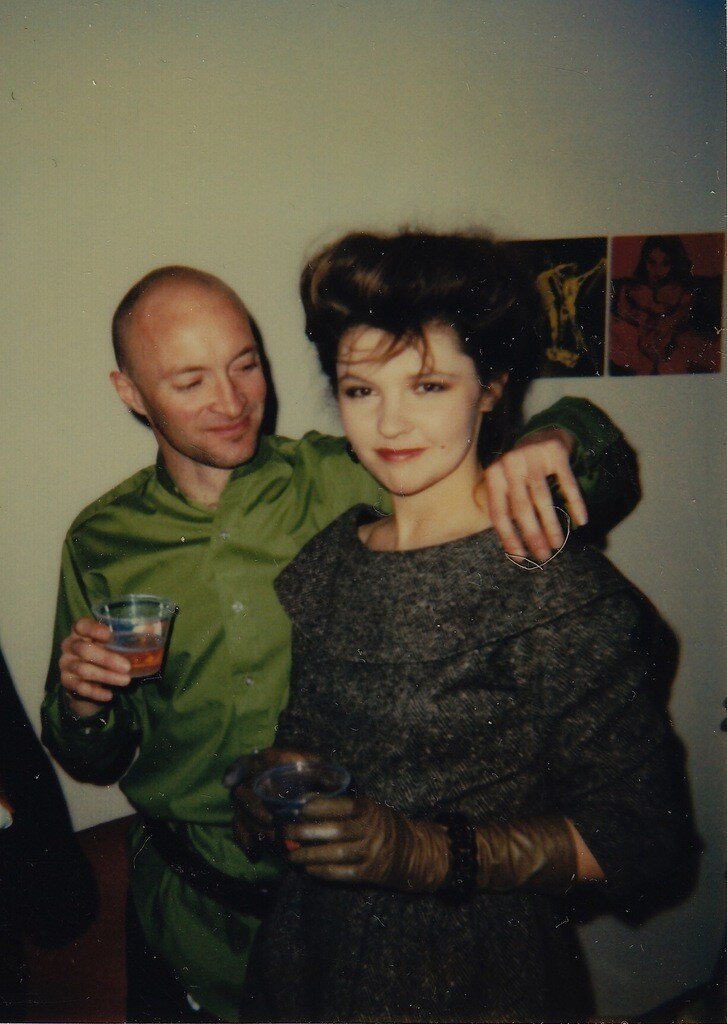

To illustrate the work of Hudson’s life as an artist and as the art dealer of Feature Inc.

Mission

The Feature Hudson Foundation (FHF) is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization fostering an appreciation and to illustrate the work of Hudson’s life as an artist and as the art dealer of Feature Inc. Our mission is to ensure the ongoing exposure to, and understanding of Hudson's creative contributions and unique vision to the arts and cultural experience by making the archives of Feature Inc. and Hudson available to museums, exhibitions, educational institutions and the general public. FHF is also dedicated to showcasing the community of artists from Feature Inc.’s iconic gallery program as well as emerging and undervalued artists through public programs, including exhibitions, lectures, conferences, performances, collaborations on exhibitions and publications.

Background

In an age when success is equated with wealth and expansion, Hudson set a different example. He built a viable business that concentrated on showing art he felt was interesting and important for us to see. Hudson was successful in the deepest sense. When you viewed art at Feature, you viewed work that mattered to Hudson in an essential way. He used his intuition and eye consistently and with a degree of trust that inspired us to understand that real connoisseurship has little to do with privilege or class. — Charles Ray

Feature Inc opened in April 1984 with an exhibition of photographs by Richard Prince and a group show including work by artists such as Sarah Charlesworth and Sherrie Levine. While in Chicago, Feature showed the work of, amongst others, Gregory Green, Rene Santos, Louise Lawler, James Welling, Kay Rosen, Haim Steinbach and Jimmy DeSana.

“He characterized Feature — so named because it was a neutral word that would not detract attention from exhibitions — as “hands-on” and an expression of a personal vision, the opposite of what he called “the current, corporate model” of galleries and “move[d] against stardom and a push for pluralism and multiplicity.”– Roberta Smith

In September 1985, Hudson presented Jeff Koons’ “Bronzes, Equilibrium Chambers . Nike posters,” followed by Richard Prince’s “Joke Paintings,” Hirsch Perlman’s “Sculpture and photography” and the first of many Charles Ray exhibitions.

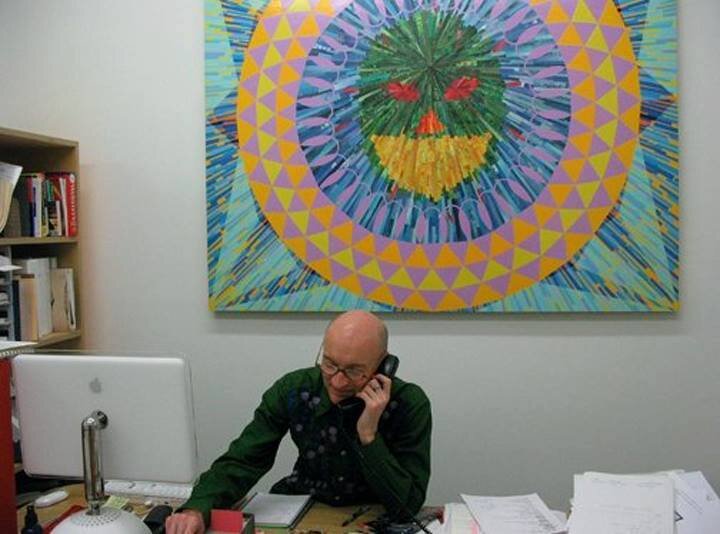

“He spurned the conventional pristine, white-cube gallery space by never walling off his offices, putting his desk up front — so he was available for questions — along with comfortable chairs for visitors. This intimate, underdone setting forced visitors to see the art for itself, free of the hyping effect of fancy architecture. Even sartorially he went against the grain. He ignored trends in art, figuring that artists who were part of them would not last. Instead he concentrated on and often gave first shows to a long list of widely respected, quietly original artists.” – Roberta Smith

Amongst many artists, Feature represented James Welling through 1987, Kay Rosen through 1995, Richard Prince through 1988, Hirsch Perlman through 1992, Charles Ray through 1997, James Welling through 1988, Raymond Pettibon from 1987 through 1994, Jim Shaw from 1988 through 1995, Tom Friedman from 1990 through 2005, Huma Bhabha from 1991 through 1998, Vincent Fecteau from 1994 through 2004, Takashi Murakami from 1996 through 1998 and Dike Blair from 1997 through 2007.

Hudson approached art not from taste or preference but from aesthetic judgment. This sounds simple, but it isn’t, because his engagement with artwork was a dynamic, ongoing, and challenging process. He had confidence in his ability to see what he recognized as interesting art. Artists working with him felt this and found that the success of an exhibition at Feature had less to do with sales than with the work’s ability to stand on its own and find its location in the art world’s arena. It was incredibly valuable for artists and also collectors and viewers to find courage to create a relationship to what they made, looked at, or collected. Hudson’s success is measured in the intellectual and artistic wealth he gave to others.

Hudson’s complexity was both internal and external. He was very private yet public. He sat in his gallery at the front desk. Every day. If you called, he was often the man who answered the phone. You had a great sense that he not only ran his gallery but that it was he who looked, in the deepest way, at the art he showed. It was he who learned and grew with what was on his walls and exhibited in his space. I am sure those closest to him could separate the gallery from the man, but there was a relationship between the two that only develops when a person is present to what they do. It’s easy to say that his interest was not commercial, but I think when we consider his life and define his gallery and interests as “alternative” we simplify a complex man. His contribution was mainstream. — Charles Ray

Contact

Feel free to contact us with any questions.

Email

mail@featurehudsonfoundation.org